Historic Performances: 10 October

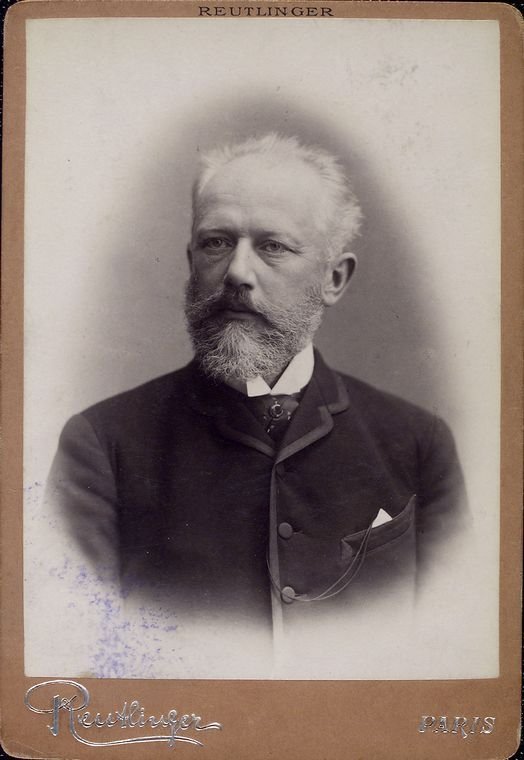

Courtesy of the NYPL. Public domain.

Historic Performances: 10 October 2021

Tchaikovsky: Piano Concerto No. 1 in B-flat minor; Sapellnikoff, Chapple, Aeolian Orchestra (apr, 1926)

Brahms: Horn Trio in E-flat major, Op. 40; Brain, Busch, Serkin (Beulah, 1933)

Schoenberg: Chamber Symphony No. 1, Op. 9b; Horenstein, Southwest German Radio Orchestra (Pristine Classical, 1957)

Weber: Piano Sonata No. 2 in A-flat major, Op. 39; Cortot (Music & Arts, 1939)

Rubinstein: Etude in C major, Op. 23, No. 2; Sapellnikoff (apr, 1920s)

Glinka-Balakirev: The Lark; Sapellnikoff (apr, 1920s)

Program Notes

Tchaikovsky's B-flat minor Piano Concerto has enjoyed a colorful performance history. Nikolai Rubinstein, Tchaikovsky's preferred soloist, at first criticized the piece so viciously that the premiere was instead given by Hans von Bülow halfway across the world, on tour in Boston in October 1875 (Rubinstein, having evidently changed his mind in the meantime, conducted the Russian premiere a month later). [1] Fast forward to the inaugural International Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958, where the concerto became an emblem of both cultural rapprochement and American artistic triumph: the recording that Van Cliburn made subsequently with Kirill Kondrashin remains one of the best-known and bestselling classical albums of all time. More recent contentions have—in line with the spirit of our times—arisen over authenticity, with Kirill Gerstein unearthing the 1879 version of the concerto which predates revisions made by Alexander Siloti. [2]

The first recording of the concerto was made by Vassily Sapellnikoff (1868-1941), an Odessa-born pianist who was discovered at age eleven and thereafter supported by Anton Rubinstein. After completing his studies with Sophie Menter, a distinguished pupil of Liszt, Sapellnikoff performed the B-flat minor Concerto under the baton of Tchaikovsky in an 1888 Hamburg concert. He quickly became the composer's favorite soloist, and the two toured Europe together for the next few years. In 1926, Sapellnikoff set the concerto down on disc for Vocalion, a label founded by the Aeolian Piano Company (and incidentally better known in its day for so-called "race records" of blues and jazz). [3] The playing is measured and unflashy, and Sapellnikoff's interpretation is on the whole not dissimilar from more contemporary performances.

Brahms completed the E-flat major Trio for Piano, Violin, and Horn, Op. 40, in 1865, following the death of his mother. The work is scored for the natural horn rather than the valve horn; Brahms had played the former in his youth and favored its fuller sound and pastoral connotations. [4] In a recording originally made for HMV, we hear the familiar duo of Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin joined by Aubrey Brain (1893-1955), who was principal horn in the BBC Symphony Orchestra and the father of the horn player Dennis Brain (1921-1957).

Written with quartal harmony, Schoenberg's Kammersymphonie was a musical landmark, albeit one that, alongside the abridged premiere of Berg's Altenberg Lieder, provoked riots at the notorious 1913 Skandalkonzert. [5] In the recording here, Jascha Horenstein employs a full orchestra in lieu of the original scoring of fifteen instruments. A conductor ahead of his time in many ways (he was an early advocate of Bruckner and Mahler), Horenstein championed the music of the Second Viennese School, introducing Wozzeck and the Altenberg Lieder to Paris in the early 1950s.

Carl Maria von Weber's A-flat major Piano Sonata, like its three long-neglected companions, forms the substantive bulk of the composer's piano oeuvre. The opening of the first movement, extraordinarily reminiscient of Chopin's A-flat major Nocturne, sets the mood for a piece suffused with a gentle, embracing warmth. For the most part, I agree with Bernard Holland that Weber's vernacular was fundamentally of the eighteenth century. This is decorous, genteel music "anchored by a sense of order...a pervasive steadiness of motion." [6] The moments of passion rarely depart from the well-tempered tempestuousness of early-to-middle-period Beethoven. Yet there are imaginative flights—for instance, fanciful passages of cascading right-hand ornamentation in the first movement—that reveal glimpses of something wilder and less mild-mannered. Cortot's playing is marked by a characteristic clarity of line, with a lightness suggesting that he too knows we are with Weber only on the cusp of Romanticism. The tempi permit a sense of flow, and tasteful dabs of rubato allow us to feel the waxes and wanes between long phrases. This is a definitive recording of music that is all too little heard, and even more rarely so masterfully interpreted.

We conclude with two "encores" by Sapellnikoff: a balletic performance of an etude by his mentor Anton Rubinstein, and a surprisingly fast-paced but incomparably graceful rendition of the Glinka-Balakirev classic "The Lark".

Kevin Wang is a producer for the Classical Music Department and the host of Historic Performances on Sundays from 6-8 PM.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Piano_Concerto_No._1_(Tchaikovsky)

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/01/arts/music/list...

[3] https://the78rpmrecordspins.wordpress.com/2013/02/...

[4] https://www.hyperion-records.co.uk/tw.asp?w=W4177