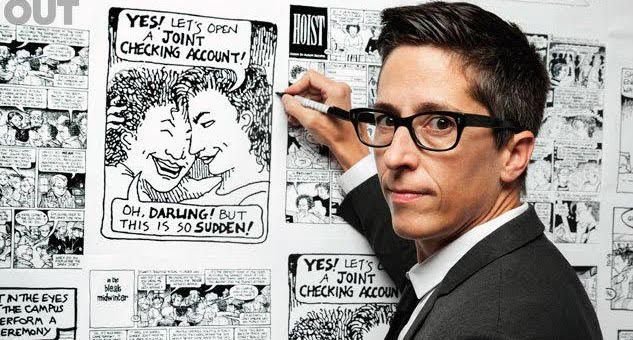

On Personal Expression and Comics with Alison Bechdel

Listen

Noelle Chung: Thank you so much for joining me today, Alison.

Alison Bechdel: Oh, my pleasure, Noelle.

NC: I’m sure – and – I hope that most of our audience knows who you are, would you briefly introduce yourself to our listeners in case anyone is unfamiliar with your work?

AB: My name is Alison Bechdel. I am a cartoonist probably best known for something called the Bechdel Test, which we can discuss if you like. Also, I wrote the graphic memoir Fun Home, which is something taught in a lot of colleges, that might be how your audience might know me.

NC: Well, first, I wanted to delve into the topic of comics. I was wondering if you had a particular favorite comic that you've done or a particular favorite panel or page among your pieces?

AB: Oh, gosh, that's an interesting question. You know, I feel like the way I feel about my work is I'm most excited about whatever I'm doing in the moment. There are many things in my past work that I like, but it loses a certain charge once it's done. I don't feel as excited about even really good stuff I've done if I compare it to whatever I'm engaged in at the moment,

NC: So what brought you to the world of comics? Or more broadly, even storytelling?

AB: Well, like most children, I started drawing as soon as I could hold a crayon. I always really loved drawing. I also begin writing as a little kid. As most children do, or almost everyone I know, wrote a novel when they were six or seven. But somehow, we all sort of set those things aside. But I didn't, I kept writing and kept drawing, and I really loved doing those things together, I like to tell stories with pictures. When I found out I could do that, I was very excited.

NC: What do you find most easy to draw? Or do you have anything that's particularly difficult for you?

AB: I find landscapes difficult. I've always preferred drawing people. When I was a little kid, I would just draw an individual person, right in the middle of my 8.5” x 11” sheet of typing paper that my parents kept supplying me with. I’d draw a person, throw the paper aside, draw another person on another piece of paper, and my dad would say, “why don’t you put some backgrounds here? Why don't you put your people in a situation?” I never was really very interested in that. Even now, as a professional cartoonist, I find those backgrounds less interesting than the characters that I'm drawing.

NC: Do you save landscapes for last? What's the overall process of planning a comic? Do you make the plot first? Or do you start with blocking out your panels?

AB: I do start with blocking out my panels. I sort of I write in Adobe Illustrator, which is a drawing program. I map out a panel grid on my page, and then I start typing words in little boxes, either as dialog for my characters or narration. I'm not actually drawing because I'm… typing. I'm doing this on the computer. I sometimes do a little drawing in Illustrator, but the tool to do that with is very tricky. I don't really like using it. I feel like it's a kind of drawing, but if you saw me you would think I was just typing. Sorry. That's kind of really boring. Unless I can show you… which I can't on the radio.

NC: Unfortunate that there’s no visuals. Well, concerning memoirs, your graphic novels get pretty personal, from your complicated relationship with your father in Fun Home to explorations of exercise in your life in The Secret to Superhuman Strength. I'm curious how you sift through all the complexities in your life and decide what specifically you're going to write and draw about. What draws you specifically to share?

AB: My Catholic upbringing and the Sacrament of Confession. That was a very profound experience for me as a young child, this idea that you could get forgiven for all your sins if you just confess them. I think I'm still trying to recreate that feeling of purity and release that I had when I made my first confession at seven-year-old by just confessing everything I can think of to anyone who will listen. I'm being a little flippant, but I do think that that's where part of that impulse comes from. I also feel like it's my way of keeping track of myself. On some deep level, I feel like no one was keeping track of me perhaps as a child, so I had to do it myself. Even though it's no longer necessary, I'm still doing it. In my work, writing these books about my life is my way of just, I don't know, keeping track of myself.

NC: So there's a large cathartic aspect to why you're doing this?

AB: Yes, large cathartic aspects and large neurotic aspects. I like to think I've found a… constructive way to harness my neuroses.

NC: Could you tell us about overall the themes you like exploring your works? What do you like to focus on?

AB: I guess my biggest theme, perhaps, is the self. Just because I feel like I have a sort of mild disorder of the self. It's made me very curious about how our selves are formed, what the self is, how to make ourselves bigger, how to let go of the very idea of the self. I think that's kind of my subject. I used to feel that it was sort of pathetic, like all I can write about myself. But it isn't, if you think of the self as also being about getting beyond the self. It’s not quite so narcissistic.

NC: Well, also in relation to the self, I've noticed that a lot of your work also explore the theme of literature. I've seen you reference Camus and Joyce and Fitzgerald and more. So how would you say literature was important to your life? Why do you use reading and tax as almost a metaphor for your life experiences?

AB: Well, another flippant answer is that my individual life isn't that interesting. But these other people had very interesting things to say and to write about, so I just copy them. But a more genuine answer is that this was the way that people communicate it in my family. My parents were both English teachers, they both love literature and poetry. They were not touchy-feely people. They connected and expressed emotion was through books. What books and stories and authors my parents liked was a way for me to connect with my parents. That still remains for me a way to access my own feeling is through other people's writing.

NC: Wow, it’s very interesting that books had that dual usage in your texts of acting as metaphors and also a little peek into your family life.

AB: Yeah. My father in particular would always try to force me to read books as a child. My way of rebelling – and this is as rebellious as I got – was refusing to read Walt Whitman. I always feel sort of angry at my dad from completely ruining Whitman for me. But I did much, much later come to Whitman on my own, a long time ago.

NC: What was it like reading those books again, those ones you were one so stubborn against reading?

AB: I actually started reading them as an exercise as I was writing Fun Home, a memoir about my dad. When I started writing the book, he had been dead for 20 years, about half of my life at that point. I felt like I was forgetting who he was. I decided this was a great bunch of material, all these authors he had wanted me to read. I would start reading them. But one exercise I created for myself was to read in particular the poetry that my dad loved, and I read it out loud as if I were reading it to my father. It was this surprisingly intense experience that would always make me cry. I feel like I really understood the poetry in a vivid way that I wouldn't have if I were just kind of reading it for myself. So, that was like a writing exercise, but also some other kind of grief work that I was doing that was very productive.

NC: Your graphic novels definitely tend toward the extremely personal and explore some deeply emotional moments, both for you and the rest of your family. How would you describe the process of sharing something so closely related to yourself, especially your childhood, when you're sharing this with the rest of the world to consume?

AB: I don't really know how to explain this. I clearly have some sort of exhibitionistic streak. But in real life, I don't feel like I do. I feel like I don't seek out attention. I'm quite shy. But I guess this is the way I do it. This is the way I get attention. An almost bottomless need for attention. Although in recent years, I've gotten so much attention. So much actually that I feel like that need has gotten met, which is interesting. I wasn't sure that was humanly possible. But apparently it is. In fact, the current project I'm working on is not kind of a memoir, but it's veering away from memoir because I just feel like I've revealed enough. Yeah, tapped out.

NC: I'm also curious about Fun Home in particular, which took off in quite the frenzy and has a number of derivative works, most famously the Broadway musical. What's it like seeing a piece of art that's directly inspired by your piece of art and just watching an artistic creation about your childhood?

AB: It was a magical, and I haven't really come up with language to describe that experience. I think six, seven, eight years out from the first time I saw that play, but I still don't know how to talk about it. I love the play. I love what these people made from my story. I felt like they made not just an adaptation of Fun Home, but they made a different version of Fun Home out of the same material. But in this new medium, in the form of a musical which has its own magic, it felt true to my story in my life. It was kind of a gift, you know. It was a way of seeing my parents both come back to life. The musical didn't happen until after my mother had died. It opened within a year after her death. It was this kind of in the middle of my grief for her. Then she got reincarnated, this wonderful actor singing this beautiful music. It was the great gift.

NC: That reminds me, what would you say that comics and graphic novels can do that the traditional literary texts cannot. Other than your love of drawing from even at a young age, why do you think that comics are special for sharing your stories with the world?

AB: There's just something that happens when you combine words and pictures. Books are wonderful too. Books take us, transport us, transform us. But when you have a picture too, there's just so much more directly into your bloodstream. I think there's less the language that we have to decode in our minds. With an image, there's no decoding it's. You just see. You see people getting on a train or someone walking in the woods. You immediately understand what that is. You don't have to decode it. There's something about that directness. Then some kind of exponential thing happens where I feel like meaning can be kind of exploded more than it could be with just a picture or just words. You bring them together. Some kind of fusion happens that's just magical.

NC: I should bring up the Bechdel Test. Could you describe what it is to our audience and also your relationship with it?

AB: I have a very sort of oblique relationship with it. It does come from something I wrote, but I never sat down and declared that this is the Bechdel Test. I wrote a comic strip many, many years ago. My first phase of my career was writing and drawing a comic strip called Dykes to Watch Out For, which I started back in the 1980s back when that was some very marginal, strange thing to do. I wrote comics about me, my lesbian friends, and the kind of things we were thinking about. One of these early comic strips was about two women who wanted to go see a movie. But all the movies were these crazy superhero movies like Conan the Barbarian. One of the women says, “here's my rules for seeing a movie.” I should say this isn't my idea. I stole this from a friend of mine at the time. This woman says, “I can only see a movie if it has at least two women in it who talked to each other about something besides a man.” These are very, very basic requirements, but hardly any movies met them in the 80s. The only movie in the cartoon that they can go to see was Alien, because the two women talk to each other about the monster. Anyhow, somehow that cartoon has had a second life as this sort of metric for how female characters are treated in a movie or a book and whether they're treated as fully human subjects.

NC: It’s fascinating how something so marginal blew up. Speaking of marginal, I want to say that comics nowadays are a lot more accepted into mainstream culture and are now taken a lot more legitimately as an art form. But to any of our listeners who still feel dubious about that, do you have a message to anyone who's still isn't sure about if they should be reading comics, or how and why they should be reading them?

AB: I don't like to persuade people. If people don't want to read comics, I have no interest in forcing them to do it. I think people should do what they're drawn to. Just if you haven't spent time looking at comics, you might want to just pick some up at the bookstore and flip through them and see if anything pulls on you. Give it a try. It does.

NC: Where do you hope to go with comics in the future?

AB: You know, I have no interest in real formal innovation. I just like telling my stories with pictures. I hope I just get to keep doing that for a while.

NC: Before we go off, do you have any final words for audience? Anything you'd like them to know?

AB: My mind is going blank because there's so we all need to know and do. The world is going to hell in a handbasket. I hope everyone's going to be okay. We just hope we're all going to be okay.

NC: Well, I hope so too. With that, I want to say thank you so much for speaking with us today, Alison.

AB: My pleasure. Thank you.

Noelle Chung, ‘25, is a reporter for WHRB News. Follow her on Twitter @Noelle_Chung_ . For any questions and news tips, please email news@whrb.org. Tune into "As We Know It" on Sunday at 1:30 p.m. ET for more stories like this one.